Ioannis Focas (Juan de Fuca) the first European to explore far latitudes off Canada

Ioannis Focas (Juan de Fuca) the first European to explore far latitudes off Canada

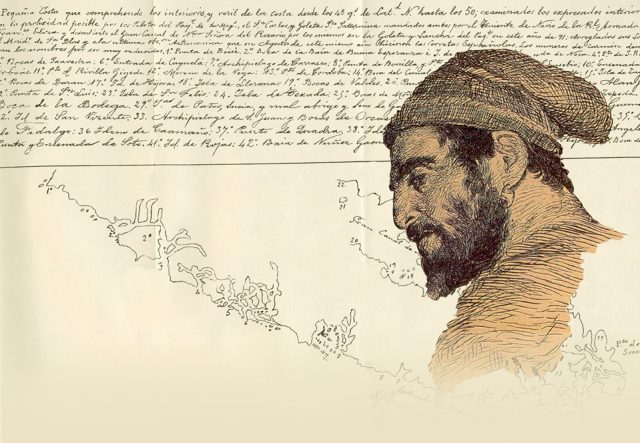

Evridiki Livada-Duca tells the true story of the Greek navigator Ioannis Focas or Juan de Fuca, the 16th century Ulysses.

In Venetian-occupied Kefallonia of the 16th century, trying to recover after the troubled period of constant change of rulers, Ioannis was born around 1530 in Valeriano, in the area of Elios. The Foca family was imperial Byzantine and first appeared in recorded history during the 5th century. Members of the family held key positions in Constantinople, in Crete and in Peloponnesus.

In Kefallonia the founder of the family branch, Emmanuel, was moved to the island after the Fall. He had four children who served in high posts. One of them was Iakovos (Jacob) father of Ioannis (John), whose full name was Ioannis Apostolos Focas Valerianos. The name Valerianos was added to the name Focas later. It is not known whether it meant to signify origin or intermarriage with the Valeriano family, another noble family from Constantinople, the presence of which in Kefallonia is verified from the 16th century and which gave its name to the settlement Valerianou village (Valerianou means in Greek belonging to a member of family Valerianos.)

As a pure Odyssean figure, fascinated by the sea, he left on Venetian ships for known and unknown ports, the fame and wealth of which had surely inflated his adolescent fantasy and aroused his sense of adventure.

Venice was the place that gave form to his dreams. So his decision to follow this course brought him before 1550 from the Venetian oar-galleys to the Spanish sailing-ships with the cross-navigation, great power of the oceans, and a mighty challenge for him. In his new home he had to adjust his name to local ears. So on his way to the adventurous and exploratory routes of the uncharted seas, he was renamed Juan de Fuca, or Juan Griego.

All Greeks who excelled in any area were called Griegos, especially those employed in sea voyages. In those years the world-dominating Hapsburg Spain attracted the fortune-hunters of many races. Among this crowd, those few, the prized pilots, or maestre or high rank mariners added to their name the characteristic: Greek, El Greco, El Griego, Griego.

Juan mainly sailed between America and Spain crossing successfully the Sea of Darkness, as the Atlantic was initially known. (Later, after the first expeditions, it was renamed Mar del Nor).

In 1552, after his marriage to a woman of Palos de la Frontera, he took the exams – along with seven others – to become Piloto de las Indias, a qualification gained in 1561.

In fact we find him sailing as maestre in different ships, La Trinidad, Sta Maria da Begonia, between Spain and Central America. During the 1570s and 1580’ he sailed between Peru and Chile in Mar del Sur – Sea of the South, Pacific Ocean- transporting silver and gold from the mines of Potosi, always serving the Spaniards.

On October 7, 1571 an important event took place in his life. Juan called was among other mariners to serve on the Reale, the main flagship of the united Christian fleet during the decisive Naval Battle of Echinades, known as the Naval Battle of the Gulf of Lepanto.

On Friday, December 5, 1578, the Elizabethan corsair Sir Francis Drake, who had already invaded the regular monopolistic merchant routes of the Spaniards in America, met the Spanish ship Capitana / Los Reyes in Valparaiso. Drake, after plundering the ship, took Juan Griego “very famous navigator in all the coast of Chile” to sail his ship along the dangerous and unknown to him coast. On February 26, 1579 Drake released the famous navigator in the port of Callao.

Ten years later Juan underwent another incident with a corsair which, this time cost him -besides his abduction- the loss of 60,000 ducats, his personal property. In 1588 as the Greek traveller returned from Sinus Sinarum – the China Sea- his galleon Grande Santa Ana was seized by the English corsair Thomas Cavendish who put the crew ashore but kept Juan as prisoner until he found a way to escape. The amount of 60,000 ducats for those times seems huge. Top-ranking sailors earned high salaries and acquired in parallel great wealth in the colonies on their own, in many ways. Juan sailed the same routes for 40 years, the Pacific and the Atlantic.

At this time the rumour of the existence of the Straits of Anian -an “invention” attributed to Giacopo Gastaldi- which it was believed united the two oceans at the North, was already well known. Until then, attempts to discover them not only had failed, but as many souls had been lost in the frozen northern seas, scared even the tougher seamen who were certain that those were voyages of no return.

The viceroy of New Spain, Mexico, found out that the English were following Magellan’s route and while he believed the transporting of gold in the western side of South America was safe, suddenly faced attacks by Elizabeth’s corsairs, Drake and Cavendish. So another safe route had to be found for the shipments. The rumour of the northern passage was known to him as was the name of the mariner Juan Griego. Therefore, he proposed the exploration and fortification of the north passage offering high rewards. All this of course had to be done clandestinely as the explorations at that time were state secrets.

The venturesome Greek accepted eagerly the challenge of the viceroy’s ambitious plans, although he well knew the dangers. Navigation up to the Arctic was something nearly impossible with the means available at the time. But from the result it seems he had strongly developed the special instinct that suggested subconsciously preservation, safety and return.

The first attempt to discover the mythical Straits of Anian was abandoned. Juan set off again in 1592 from Acapulco with a small caravel and a pinnace, as tender boat, manned by obedient, daring and experienced sailors. He sailed around Mexico from the west, around the coastal mountain ranges of California and braved the entry into a north-eastern opening of the land. He sailed this unknown passage for twenty days. It was located between the 47th and 48th parallels, narrow in places, wide in others, and dotted with many islands. He noted the presence of a characteristic pointed post, that the natives were numerous, dressed in animal skins, and the area seemed fertile and rich. Bad weather, the weariness of crews and ships obliged Juan to return. Focas and his crew sailed into history and unknowingly discovered not the non-existent Straits of Anian, but the straits south of Vancouver Island.

His reward for opening new horizons was limited to praise and glory in Mexico and Spain, so he decided to return to his homeland.

In 1596 he found himself in Florence where he met the English mariner John Douglas and through him met in Venice the English consul in Aleppo, Syria, Michael Lok, to whom he recounted his discovery, the loss of his property to Cavendish and his grievance against the ingratitude of the Spaniards.

When Lok met Focas he was already a cartographer, a collector, and voyage financier for uncharted seas. He also dealt in commerce and had close contacts with Elizabeth’s court. Focas asked Lok for a 40 ton ship and a tender and promised that in 30 days he would sail through the straits. Lok who at that time had not the economic capability himself to finance Focas’ trip, immediately wrote three letters to the Elizabethan treasurer – minister of finance and general secretary William Cecil, to Sir Walter Raleigh and to the famous geographer Richard Hakluyt relating the story told by Focas, his demand for returning the property lost to Cavendish and the advantages for England if they exploited such an opportunity. It is of course reasonable that if Lok did not trust Foca’s story, being himself an important person, he would not compromise his reputed name to such great personalities giving non-important information.

Fifteen days after their meeting in Venetia, the Kefallonian left for his island from where he started to correspond with his English friend. He informed him that he was ready to face the already sailed route, having recruited his crew, 20 men from his own village who were eager to take part in the great adventure.

The correspondence continued for almost six years. And when finally the money was found Lok went to Zakynthos from where he sent the last letter informing Focas to get ready to leave with him for England. But on June 1602 severe illness then death reached the Kefallonian mariner, without him fully knowing what lands he had discovered.

Πηγή: http://www.allaboutshipping.co.uk/2019/10/22/ioannis-focas-juan-de-fuca-the-first-european-to-explore-far-latitudes-off-canada/?fbclid=IwAR2lu9S5vcT-xkmqb1_FnNhVIAJMjwv3Xe9FHunVBDnTuzxBrUDNxy0LzRI